Capstone Project

Picking up a phone call from her daughter, Yolanda Jennings hears the five words that change her life forever: “Something has happened to Colin.”

Not knowing what to do next, Jennings scrambles to find out more information. After hitting dead ends with both hospitals and the police department, Jennings turns on the news to learn her 26-year-old son has been shot and killed by police.

“I was hysterical,” said Jennings.

Later Jennings learned the details of what had happened. Following a 911 call, officers showed up outside of Colin’s apartment. As he came outside, holding a knife, he continued to yell “kill me” over and over until police simultaneously tasered and shot him.

Colin’s story is the latest of a concerning pattern within the Columbus police division. The department has a long track record of police violence in Columbus, with more shootings per arrest than 99% of departments across the country, a Lantern analysis of arrests data shows.

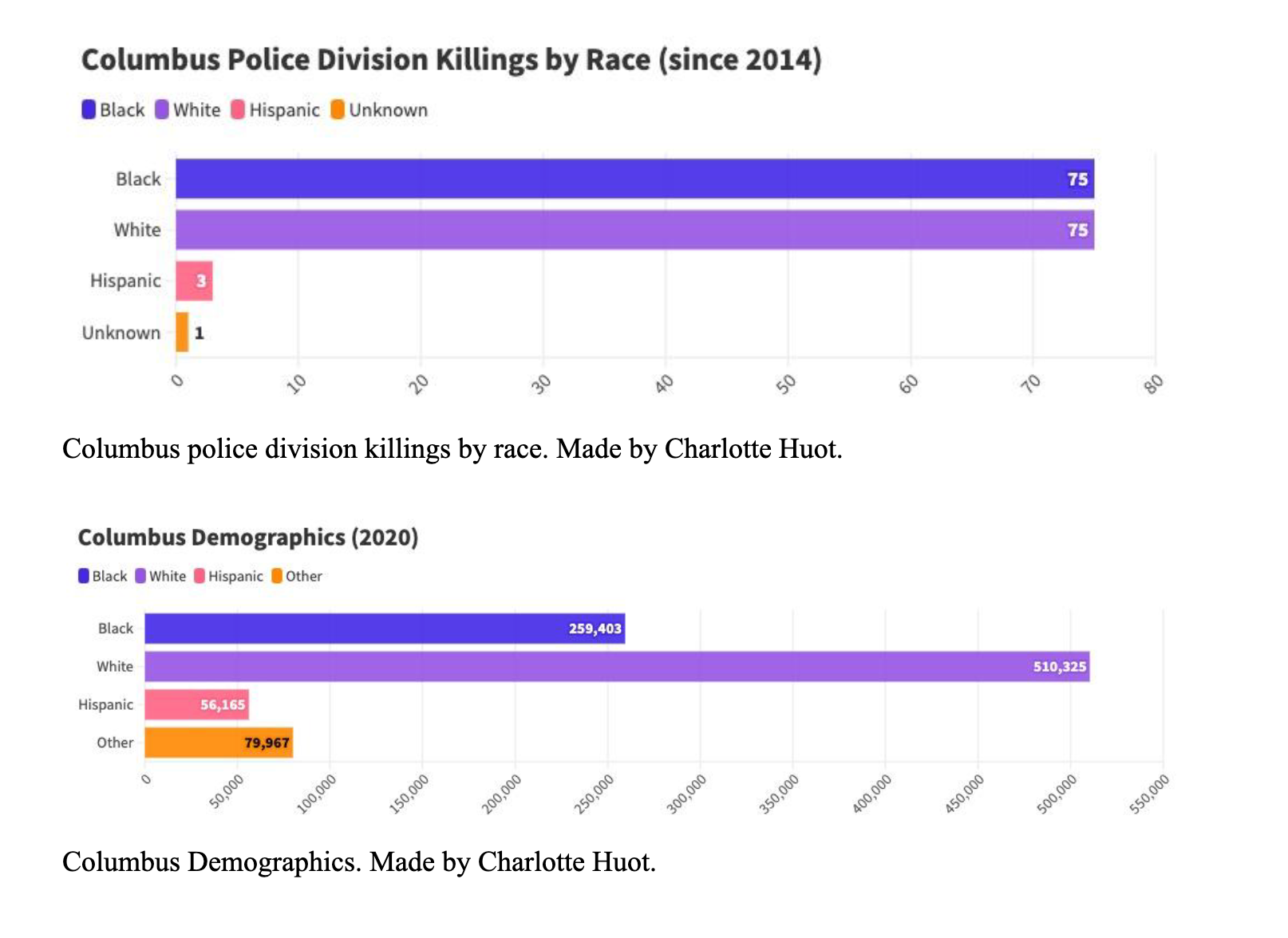

Of those force cases, comparatively to Columbus census data, being the victim of a police shooting is twice as likely to happen to people of color than those who are white.

Police say it’s unfortunate, but force is required in certain situations. Vice president of the Fraternal Order of Police, Brian Steel said from a police perspective, force is warranted a lot of the time.

“The overwhelming majority of use of force cases, it boils down to resisting arrest or fleeing,” said Steel. “It's unfortunate what happen[s].”

Groups like Columbus families unite against police brutality are fighting for reform in order to prevent more violence, especially in Black communities. Its CEO and founder, Sabrina Jordan created the organization after her son, Jamarco DeShann was killed by the Dayton police in 2017.

“Columbus is one of the deadliest police forces in the country,” said Jordan. “And we're in a Democrat-controlled city that could absolutely take more steps towards accountability, if there were the political will to do so.”

With the Columbus police division being both the largest department in the state and one of the deadliest in the country, the justice project in Columbus has also been working towards reform, most recently advocating for a non-police emergency response system, according to their director of operations, Emily Serafy-Cox.

“Those [mental health crises] are not situations where police should be showing up,” said Serafy-Cox. “And so that's really what we’re concentrating on, trying to divert situations away from policing, where there is a higher risk for violence.”

This overwhelming use of force used by the Columbus police division is not new and continues, with two people, including Colin, already having been killed just this year.

In the past 10 years, 56 lives have been lost to police violence in Columbus, according to data. That averages to about six people every year. Of these six, four will be people of color.

Arrest data also shows the disproportionality of people of color being arrested when compared to the demographic of Columbus. Specifically, in Columbus only 28% of the population is Black, but they make up 63% of arrests.

Police say this is because of the overwhelmingly majority of crimes being committed in lower-income areas, where there are more people of color.

“The way our neighborhoods work, the inner city challenged community colors are usually black communities of color,” said Steel. “But crime is usually driven by those areas.”

However, these communities of color are also often subjected to over policing. Serafy-Cox said from her experience growing up in a middle class neighborhood, higher income areas are still experiencing similar numbers of crime.

“I think the contention that crime doesn't happen in upper or middle income communities is flat out wrong,” said Serafy-Cox. “It's just that you know, the people that I grew up with who were committing those crimes didn't get caught the way that my friends who grew up in low income communities got caught because we didn't have over policing in my neighborhood.”

These differences in policing are helpful in understanding why black communities are twice as likely to experience police violence in Columbus. And the reality of this situation is that once someone in a family is incarcerated, those ramifications continue to echo down the line.

“It's not just disproportionately affecting the people who are arrested, it's disproportionately affecting their families and their whole community,” said Serafy-Cox. “Communities are constantly drowning, constantly not making it, not being able to make themselves whole, because they're being targeted by policing.”

This cycle primarily stems from the roots of a system built on the foundations of racism, according to Serafy-Cox. However, police say they think racism isn’t systemic.

“I believe in racism. I don't believe in systemic racism,” said Steel. “Is it systemic racism in law enforcement? Or is it systemic racism in society? If that's the case, then I have to admit that my complete makeup of a police officer is routed in racism. I just do not believe that.”

Serafy-Cox, however, has differing opinions.

“When an institution is founded in that way, it's just, it's impossible to uproot that kind of embedded system,” said Serafy-Cox. “It's like that was the foundational purpose of the institution. So why on earth would we think that that's going to change just magically?”

The Columbus division of police is no exception to this embedded system. Compared to the populations of Columbus, one in about 3,400 black people will be a victim of police force whereas every one in nearly 7,000 white people will, according to the data. In other words, Black persons are twice as likely to experience police violence in Columbus.

Growing up in this reality, it’s no wonder why people of color are distrusting of police. As a Black woman, Jordan talked about her experiences with police.

“You go from fearing the police to hating the police,” said Jordan. “There’s a lot of people out here in different communities, you know they don’t trust them. Me, I don’t. I don’t trust them. I don’t care if they have pulled their gun and shot somebody, killed somebody, or if they haven't. If you’re not whistleblowing on your corrupt-ass partners, then you're just the same.”

Violence like this doesn't help the communities relationships with police, only reinforcing the fear that many people of color are – understandably – taught from a young age.

“All the communities [where police violence is] happening, you know, they're always angry [and] mistrusting,” said Jordan. “I grew up, you know, living in the projects, and when I was a kid I remember my first interaction with a cop, and he was just calling us animals.”

It’s because of these experiences that the relationship between police in Columbus and communities of color has deteriorated to the extent it has reached. Serafy-Cox said within community conversations through the justice project, they were able to learn how people of color are feeling.

“Even one woman said, you know, if I see a police presence in my community, even if I'm not doing anything wrong, I still get nervous,” said Serafy-Cox. “I change the way that I'm acting, because, you know, because of the trauma that she has experienced before, because of stories of all kinds of experiences from her loved ones and members of her community.”

As for police accountability, Jordan in Dayton said it is rare. Legal action is almost always taken against officers involved in police shootings, however it is up to the prosecutor whether or not charges are filed.

“Even if they do actually indict a police officer, some of them still go home and get back on the police force,” said Jordan. “You very seldom ever hear about police officers really being held accountable.”

Police, however, say their profession has more than enough layers of accountability.

“We've done things through the FOP, body cameras, we now have that as an example,” said Steel. “We've made concessions in our contract, concessions with internal affairs, there are so many layers of accountability, I would argue there's no profession with more layers of accountability.”

Nonetheless, as Jordan brings up, it’s up to the discretion of leadership in the department if officers are actually being held to these standards.

“Usually, like here, I know so many police officers that just get traded to a different precinct or a different police station, just moving them around,” said Jordan.

Flash back to Dayton in 2017, Jordan’s son, DeShann arrives home from a night out with friends and decides to sit in his car to listen to music for a little longer, eventually falling asleep. While he was asleep, a neighbor made a 911 call about an unrelated car blocking their driveway.

Officers showed up and saw DeShann in his car, diverting from the original call, they began to approach him, seeing a gun on the passenger seat.

As they ran his plates, DeShann’s girlfriend and baby's mom came outside to tell the police it was just her boyfriend sleeping in his car. Upon walking outside, police held a firearm in her direction, instructing her to go back inside.

She got halfway around the building before hearing the gunshots that killed DeShann. Falling to the ground, she called Jordan, screaming “I think the police just shot Marco”.

Later, through reports, Jordan learned that her son had been shot 10 times, both through the back and front windows of his car by both officers involved.

Police say in police training, officers are taught to shoot until the threat, or person stops.

“If you fire one shot and someone stops and is incapacitated, you won that scenario, you go home,” said Steel. “Sometimes it takes four or five, six, it can take 10 shots to stop someone. I understand how callous that sounds, it does not look good, force is always ugly.”

As for responding to more delicate situations, Steel said there are some teams of officers who work with social workers to help with mental health crises.

“Where it helps us is if someone calls and says, ‘Look, I'm having a bad day, I don't want to hurt someone or myself but I don't really know if I'm meant for this world',” said Steel. “Probably better off not sending an officer there. I'm not needed.”

Police even question how to approach these situations without proper training. In regards to Colin’s death, Steel said he questions who to send for someone in a crisis.

“It's hard to wait when someone's coming at you with a knife yelling ‘kill me’,” said Steel. “The officer made the determination to fire and ended up killing him. Just based off my training experience, while it’s upsetting, I understand how it’s justified. The question for that is, who do we send? Do we send a social worker? Who else do you send?”

Back in Philadelphia where Jennings currently lives, questions about the officers involved in Colin’s death continue to circle through her mind: Will anyone be held accountable? What was the point of the taser if they were just going to shoot him? Why didn’t they wait to see if it had worked?

“We got your young people with autism who might not act or think,” said Jennings. “My son, whatever happened to him in the moments before he ran out, it was so much pressure that when he does, he acts on impulse. And I can guarantee you he really didn't want to kill himself.”

At the time, Colin was living in an apartment building designed specifically for people who struggled with mental health or chronic homelessness. Jennings questioned where the mental health staff with the police department was and why they would go to an apartment building where someone was having a crisis, without the tools to diffuse the situation.

Jennings even said that when Colin was killed, the city of Columbus was supposed to have mental health professionals for these situations, the only problem being that staff started at 10 a.m. and Colin was killed around 9:30 a.m.

Thirty minutes that determined life or death.

For situations like Colin’s, the city of Columbus had launched a pilot program in 2023 which allocated $1.2 million in order to hire mental health staff equipped for these incidents. However, still no program has been established as of now.

“[The city of Columbus] has done nothing with that money and there's no program,” said Serafy-Cox. “Here we are, more than a year after it was allocated with no progress whatsoever.”

Without another option, officers are obligated to go help with situations they’re not trained in.

“I understand mental health and I grew up with mental health in my family,” said Steel. “But people in crisis, you can't reason with them a lot of times and maybe it's not their fault.”

Right now the justice project is continuing to work towards getting the city to establish these programs in order to respond to situations like Colin’s, according to Serafy-Cox. Even Jennings questions where the money went.

“The fact that Columbus has $1.2 million that's supposed to be set aside to hire mental health staff to be able to come out in situations like this is mind boggling,” said Jennings. “There was nobody on staff. That's ridiculous. You should have people on staff 24/7. I mean, come on now, we know that after the pandemic, especially, people's mental health problems have skyrocketed.”

Colin struggled with mental health problems all his life. He was always young at heart, as Jennings described him. After being diagnosed with autism late in his life, Colin began to understand why he was different.

Jennings said Colin was full of love. He loved Disney, theater, Korean pop music, collecting fashion dolls and most memorably using his index finger and thumb to make a small heart – a Korean symbol for love.

“He was just a very loving person,” said Jennings. “Colin was my heart. You know, I love all my kids. But I spent so much of my time trying to protect him from this cruel world. And I thought him coming back to Columbus would be safer for him [than Philadelphia].”

Looking forward, 3 months after her son's death, Jennings reflects on how her life has changed.

“My life will never be the same,” said Jennings. “That was my baby. But what it's going to do is cause me to fight even more.”

If there’s one thing Jennings wants people to remember about her son, it’s the love he brought to the world.

“I wish [Colin] could have seen himself through my eyes and all these other people who saw that he was just a beautiful soul,” said Jennings. “He just wanted to be loved. He just wanted to be accepted and just be him. He was a tortured soul most of his life so I hope, I believe, that he’s finally at peace.”

Colin Jennings and his mom, Yolanda at church.

Sabrina Jordan with her son, Jamarco.

Methodology

All data used for this article was obtained from public online databases. The main resources used were the Washington Post’s police killings database, mapping police violence website and data and the U.S. census data.

The Lantern analyzed this data by taking the number of police shootings divided by the number of arrests to find how many shootings per arrests each police department in the country has had in the past 10 years. Using this number as a baseline, in order to compare the Columbus police divisions use of force against other police departments.

In order to compare and rank the Columbus police divisions use of force against other departments in the country the Lantern used this number as a baseline, finding Columbus to be in the 99th percentile, meaning they have more shootings per arrest than 99% of departments.

As for analyzing race, the demographic of Columbus was compared against the demographic of arrests by the Columbus police department. The demographic of Columbus is made up of 55% white and 28% black, whereas the demographic of people killed in the past 10 years by the CPD is 73% black and 25% white. Arrest rates are also disproportionate with 63% arrests of black persons and only 32% white.

In order to determine that people of color are twice as likely to experience police violence, the Lantern took the number of black persons living in Columbus and divided it by how many have been killed by the CPD. The same was done for the white population in Columbus.

From this the Lantern found that one in 3,458 black persons experience violence whereas one in 6,804 white people will experience police violence. With 6,804 being nearly double 3,458, it means that people of color experience police violence at a rate twice as much as those who are white.